As the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) seeks its fourth consecutive term in Delhi in the face of a stiff challenge from the BJP, with exit polls predicting the saffron party’s return to power in the national capital after 27 years, the results to be declared on Saturday will show if the ruling AAP did enough to fend off anti-incumbency or if the BJP’s all-out campaign did the trick.

A number of factors – from the presence of the Congress and other parties in the fray, the performance in Scheduled Caste (SC)-reserved seats and those dominated by Muslims to how women and the middle class vote – could determine the outcome in Delhi’s 70 Assembly seats on Saturday.

A look here at the major data points to watch out for on results day.

Vote shares

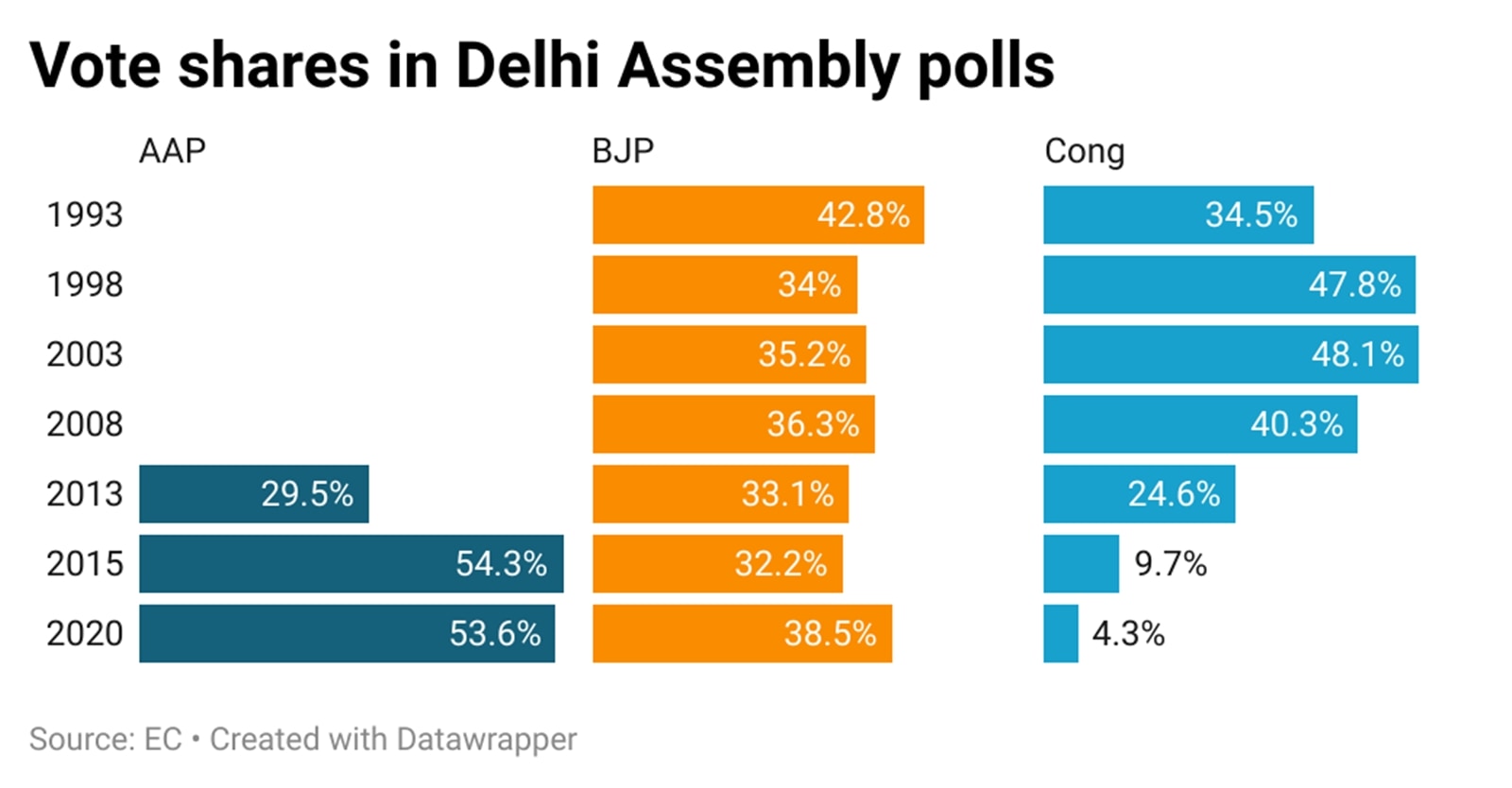

Since the BJP notched its first and only win in the 1993 Delhi Assembly polls, the first held after the capital’s Assembly was established, the party’s vote share has hovered between 30% and 40%. The party first trailed the Congress from 1998 to 2008, before emerging as the largest party in a hung Assembly in 2013 but failing to form a government, and then falling behind the AAP in the next two elections.

The BJP will draw some comfort from the considerable bump in its vote share from 32.19% in 2015 to 38.51% in 2020, even though its seats only rose from three to eight. The AAP’s vote share, however, remained stable between 2015 and 2020, going from 54.34% to 53.57%. But the BJP’s strong Lok Sabha performance last year, winning all seven parliamentary seats for a third consecutive time, will likely boost its hopes that it can break Delhi’s Assembly-Lok Sabha dichotomy this year with its pitch for a “double-engine” government.

Vote shares in Delhi Assembly polls

Vote shares in Delhi Assembly polls

However, with the Congress and AAP, members of the INDIA bloc, failing to agree on alliance terms, the grand old party could end up cutting into the AAP’s vote share. The Congress has been aggressive in its campaign against the AAP and if it is to chart any sort of revival in Delhi, it is likely to come at the cost of the AAP given that the two parties are vying for roughly the same section of the electorate. A split in this electorate could end up benefiting the BJP.

However, since 1998, the Congress’s vote share has been consistently declining, dropping precipitously from 40.31% in 2008 to 24.55% in 2013, and then again to 9.65% in 2015 and 4.26% in 2020.

Story continues below this ad

Middle class

Delhi’s middle class has increasingly become the focus of this election campaign. With the AAP admitting that it is viewed as a party solely “for the poor”, it launched a “middle-class manifesto” with a series of demands for the 2025-26 Union Budget in an attempt to link its focus on the “underprivileged” to the middle class.

However, the BJP, the party identified the most with the middle class, is also eyeing this group of voters. While presenting the first full Budget of the Narendra Modi-led 3.0 government in Parliament on February 1, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made several announcements aimed at the middle class, including declaring that no income tax would be payable up to an income of Rs 12 lakh per annum.

Given that the middle class accounts for 67.16% of Delhi’s population, or 28.26 lakh households, according to a 2022 report by the People Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE), this focus on the middle class is unsurprising.

However, in 2015 and 2020, the middle class vote was squarely with the AAP. Survey data from the Lokniti-CSDS, an independent research institute, showed that the AAP’s vote share went from 55% to 53%, while the BJP’s rose from 35% to 39%.

Story continues below this ad

The AAP and BJP have also been targeting Delhi’s Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), which are a part of the city’s landscape in colonies occupied by mid- or higher income groups.

If the BJP-led Centre’s Budget announcements find currency among middle-class voters, the balance in this crucial and sizeable section of the electorate could shift away from the AAP.

Women

Across the country, women have emerged as a crucial vote base capable of swinging elections. Most recently, in Maharashtra, the popularity of the Ladki Bahin scheme to give allowances to women helped the BJP-led coalition come to power. In 2020, the AAP’s free travel for women scheme had been key to its win in Delhi.

This time in the capital, parties have gone all out to draw in women voters with new schemes. The ruling AAP has offered monthly financial assistance of Rs 2,100 for non-tax-paying women. Countering the AAP’s scheme, the BJP and Congress each promised monthly financial assistance of Rs 2,500. This is besides other schemes aimed at women, from subsidised LPG cylinders to improved pensions and other health- and education-related grants.

Story continues below this ad

In Delhi, there are 72.36 lakh women electors. Though overall turnout has dropped in consecutive polls from 67.13% in 2015 to 60.52% this year, the gap between male and female turnout in the Capital had shrunk only marginally between 2015 and 2020.

Women, however, have been a key support base for the AAP in the last two elections. In 2015, the Lokniti-CSDS survey found that the AAP secured a 53% vote share among women, compared to the BJP’s 34%. By 2020, the AAP’s vote share among women rose to 60%, while the BJP managed 35%. The AAP will need women to stay in its corner if it is to return to power once again, though the BJP’s pro-women promises will pose a challenge.

Dalits

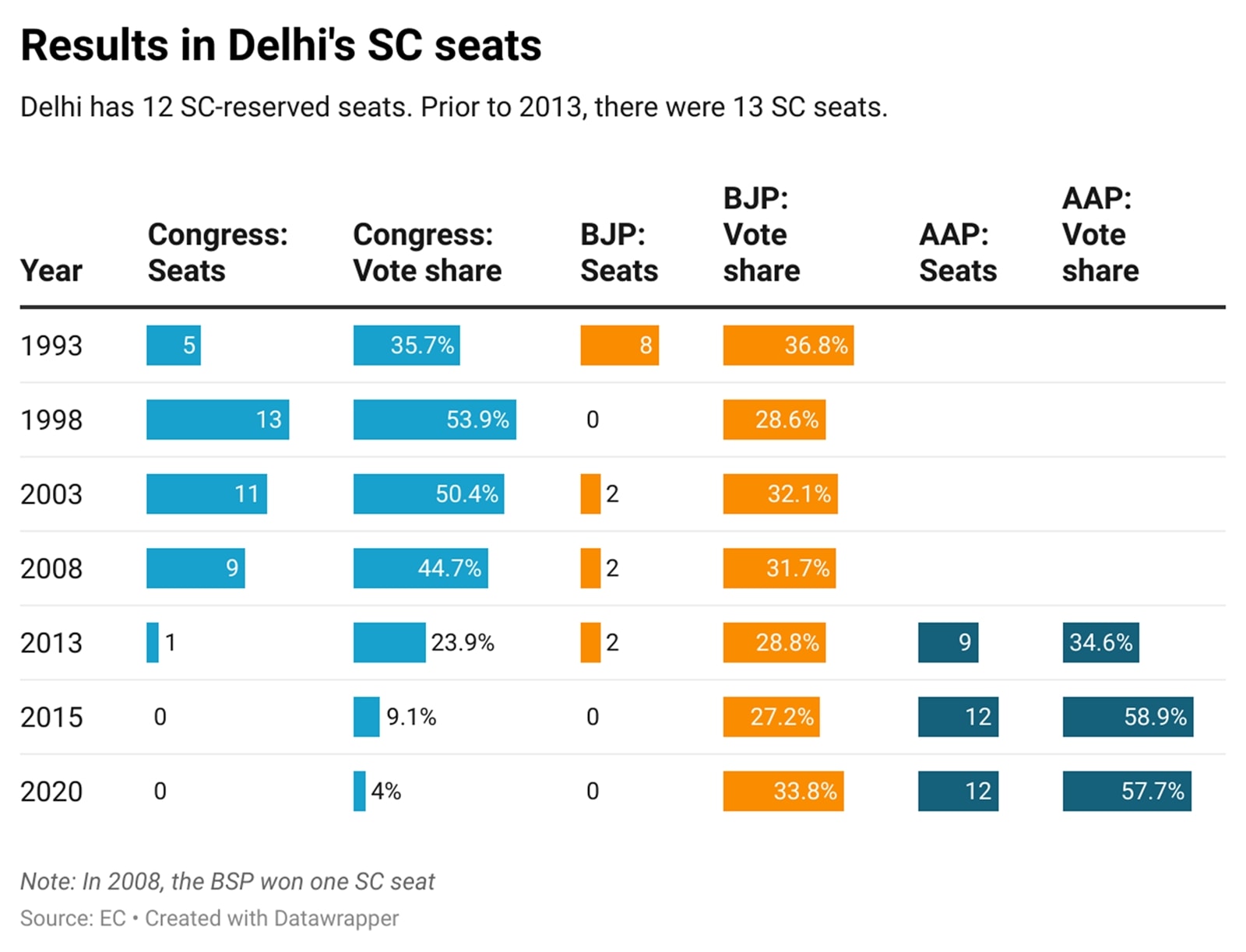

In past elections, Delhi’s 12 SC-reserved seats have largely been cornered first by the Congress and then the AAP. Since the BJP won eight SC seats in 1993, it has never won more than two reserved seats. Its vote share in SC seats is also yet to exceed its 1993 outcome of 36.84%.

Between 1998 and 2008, the Congress won a majority of the SC seats, and after 2013, it is the AAP that has dominated these seats. In vote share terms too, both the Congress and AAP have managed to secure over 50% of the vote in these seats in multiple elections.

Story continues below this ad

Results in Delhi’s SC seats

Results in Delhi’s SC seats

While the INDIA bloc’s ‘Save the Constitution’ pitch worked in its favour in last year’s Lok Sabha elections, its efficacy has waned in the state polls that have been held since. In Dalit colonies in the Capital, the Constitution is not part of the electoral discourse. Poll conversations have largely centred around the AAP government’s schemes, and the promises made by the BJP and Congress in response.

In Delhi this time, the presence of Dalit-oriented parties like Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Chandrashekhar-led Azad Samaj Party (Kanshi Ram) could dent the AAP’s dominance in the reserved seats. The Congress, too, could cut into the AAP’s vote share in these seats.

Muslims

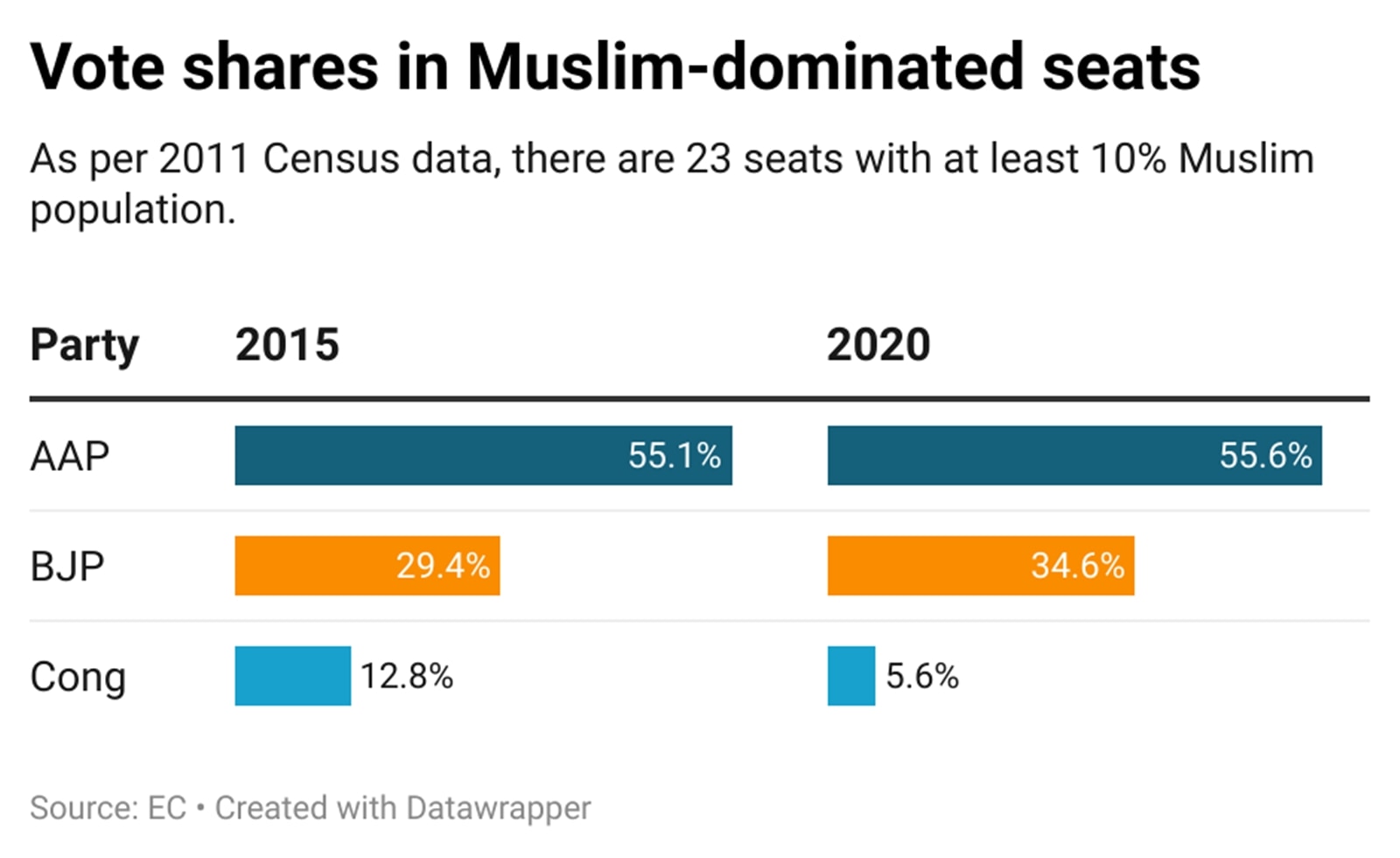

The minority vote could be decisive in Delhi, particularly in the North East and Central Delhi districts, where Muslims make up a sizeable portion of the population. While Muslims account for 12.9% of Delhi’s population, in North East and Central Delhi they account for 29.3% and 33.4%, respectively.

There are 23 seats in Delhi where Muslims make up at least 10% of the population. Between 2015 and 2020, while the AAP’s vote share in these seats remained stable at around 55%, the BJP’s rose from 29.44% to 34.57%, and the Congress’s fell from 12.81% and 5.57%.

Story continues below this ad

Vote shares in Delhi’s Muslim-dominated seats

Vote shares in Delhi’s Muslim-dominated seats

In 20 of these 23 seats, the BJP saw its vote share increase between 2015 and 2020. The AAP, meanwhile, saw its vote share drop in nine of these seats. With the AAP and Congress vying for this section of the electorate, a split in the vote could end up benefiting the BJP. The added presence of the AIMIM in two seats, could lead to a further division of votes.

In the areas affected by the 2020 riots, particularly in North East Delhi, locals were generally of the opinion that while they are unhappy with how the “AAP government acted during and after the riots”, they had no choice but to vote for the party.