THE recent incidents of attack on non-Marathi speakers in Mumbai and surrounding areas has brought the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) of Raj Thackeray back in conversation just ahead of the civic polls, which provide the struggling party a chance to remain afloat.

The attacks also tug at the son-of-the-soil sentiment which has paid dividends in Maharashtra politics in the past, especially in Mumbai with its evolving linguistic landscape shaped by decades of migration and demographic shifts.

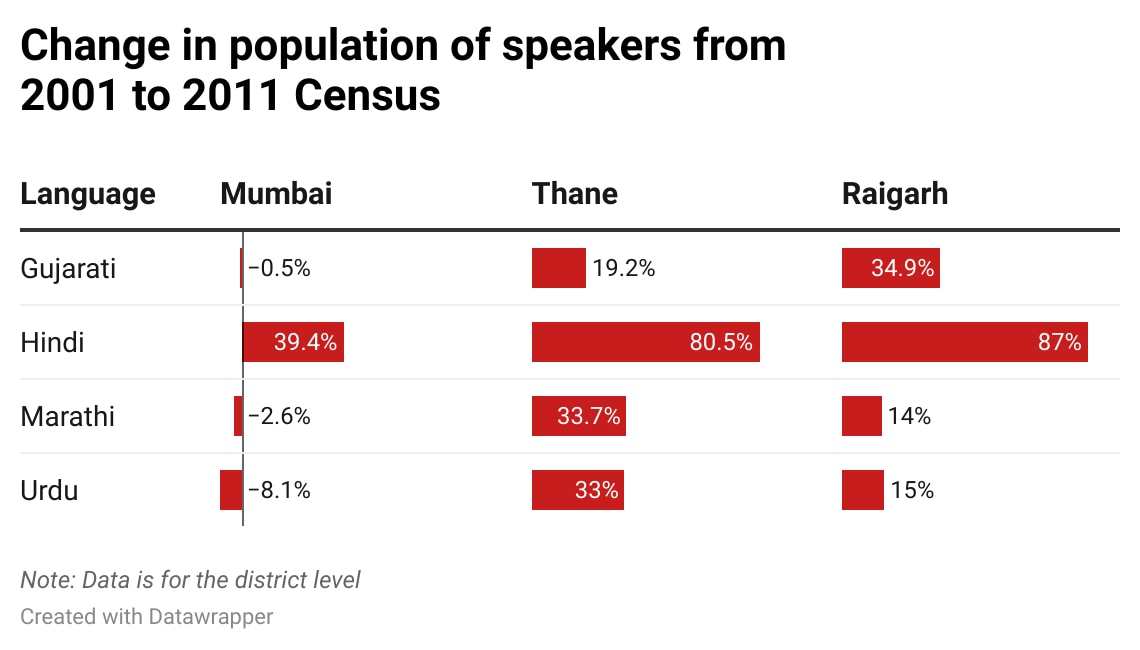

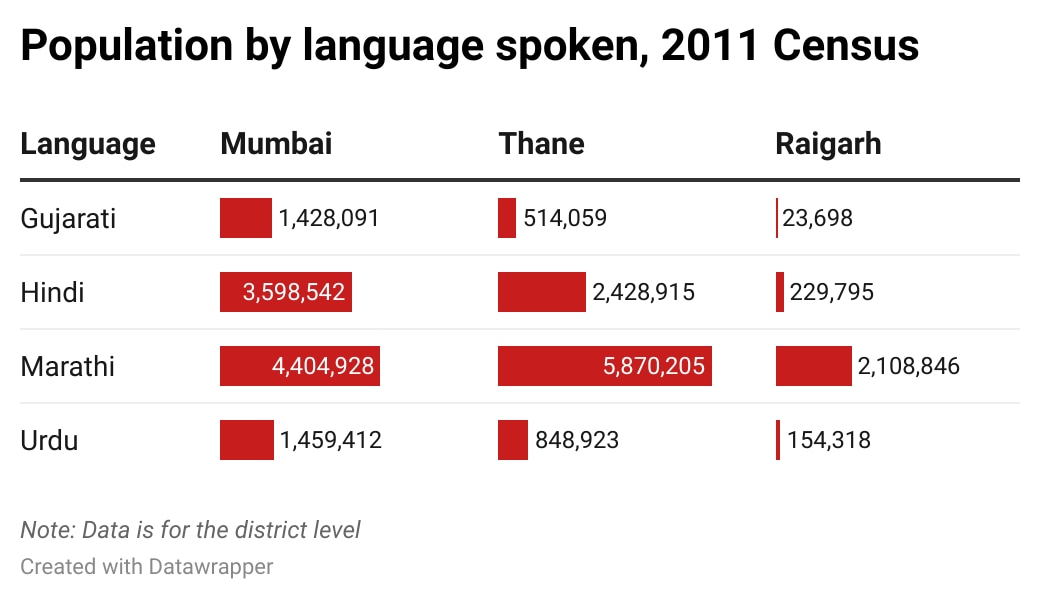

Data from the 2011 Census, the last such available numbers, reveals a significant rise in the number of native Hindi speakers in Mumbai and its surrounding districts, alongside a marginal decline or stagnation in native Marathi speakers – including in Thane and Raigad, which have seen attacks linked to Marathi.

Between 2001 and 2011, the number of Mumbai residents reporting Hindi as their mother tongue rose by over 40%, from 25.88 lakh in 2001 to 35.98 lakh; while those identifying Marathi as their mother tongue declined from 45.23 lakh to 44.04 lakh in the same period.

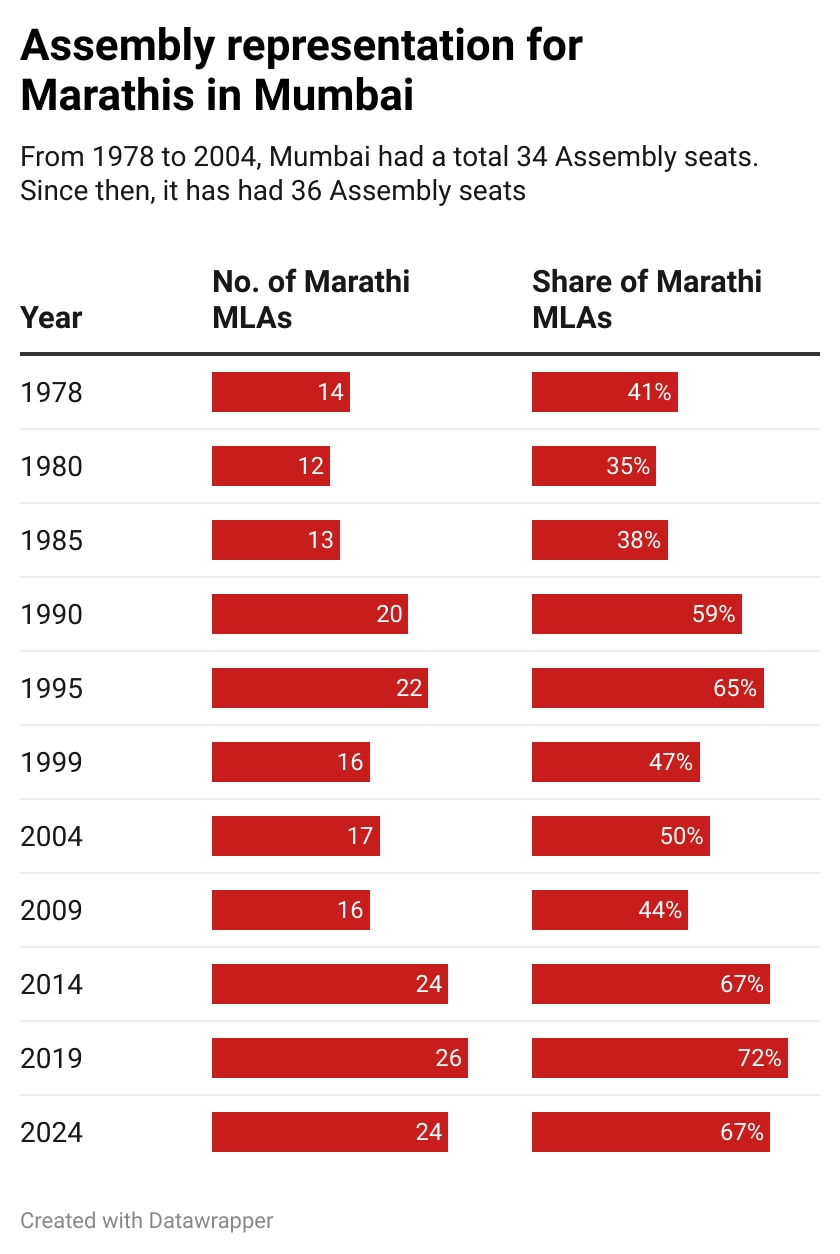

At the same time, this has not meant a proportional change in whom people vote for, with the share of native Marathis among MLAs actually rising over the years.

In his first reaction to the attacks on non-Marathi speakers, Maharashtra Chief Minister and BJP leader Devendra Fadnavis said Friday that violence in the name of language could not be tolerated. “We have already initiated action, filed FIRs. One cannot force a businessman to speak in a particular language. There are Marathi businessmen in other states as well. They may not be fluent in the local language. So will they face violence?”

The numbers

From its early days as a port city, to its rise as a textile and industrial hub, Mumbai has always been a haven for migrants. By 1921, migrants made up nearly 84% of its population, mostly coming to the city from the Konkan region, Western Maharashtra, Gujarat, Goa, and parts of the former Bombay Presidency.

As the city evolved into the financial capital of the country and home of the film industry, the trend continued. But now there was a difference. In the last four decades, which have been marked by deindustrialisation of Mumbai, the closure of textile mills and a pivot towards the service economy, the pattern of migration has changed from predominantly intra-state movement to an influx of low-cost labour from states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

Ram B Bhagat, of the Department of Migration and Urban Studies at the International Institute of Population Sciences, points out in a paper – titled “Population Change and Migration in Mumbai Metropolitan Region: Implications for Politics and Governance’ – that between 1961 and 2001, the share of migrants from the rest of Maharashtra in Mumbai declined from 41.6% in 1961 to 37.4%. On the contrary, that of migrants from UP doubled from 12% to 24% and those from Bihar went up from 0.2 % to 3.5%.

The change

Today, those who identify Marathi as their mother tongue still form the largest linguistic group in Mumbai, followed by those naming Hindi, Urdu, and Gujarati. But the dominance of Marathi has been eroding. Between 2001 and 2011, those who said Marathi was their mother tongue declined from 45.24 lakh to 44.04 lakh. Gujarati speakers also saw a slight drop, from 14.34 lakh to 14.28 lakh.

In contrast, those calling Hindi their mother tongue surged by nearly 40%, from 25.82 lakh to 35.98 lakh.

The sharpest decline was among those who identified Urdu as their mother tongue, who fell by a sharp 8 percentage points.

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

The reasons

One reason for the decline in native Marathi speakers has been rising real estate prices in Mumbai, pushing many to the city’s fringes. However, these peripheral areas have also seen a massive rise in Hindi-speaking populations. Thane saw a 80.45 percentage point rise in those naming Hindi as mother tongue between 2001 and 2011, with Raigad seeing an even sharper rise of 87 percentage points.

Some experts also believe that the sharp rise in native Hindi speakers reflects greater accuracy in self-reporting, more than a huge influx. In Census exercises before 2011, migrants, especially from Hindi-speaking states, may have downplayed their linguistic identity to avoid being perceived as outsiders, as per these experts.

Mumbai politics in the 1960s, that saw the birth and growth of the Shiv Sena, was marked by a sharp anti-outsider sentiment, though the biggest target at the time were Tamils. During the 1980s-90s, a shift took place towards anti-North Indian rhetoric, driven by growing migration from states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which put the city’s infrastructure and job markets under pressure.

This hostility has resurfaced periodically, most notably in 2008, when the MNS, just two years after its formation, reignited the issue with street agitations. While North Indian migrants have borne the brunt, even well-established communities like the Gujaratis have occasionally found themselves targeted by the broader ‘outsider’ narrative.

As Mumbai becomes more and more cosmopolitan, and there is increasing contact between people of different regions, the “outsider” sentiment is no more as powerful. People hence may feel freer to report their mother tongue more honestly, even as a mark of assertion, say experts.

A similar trend, for example, was observed among native Urdu speakers whose reported numbers surged between 1981 and 1991. This was in the period when communal tensions were rising in the wake of the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation, seeing assertion of their identity by the minority community.

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

Graphic by Anjishnu Das

The rise in those identifying themselves as Hindi speakers similarly coincides with the rise of the BJP, with its heartland base, in Maharashtra. This assertion has strengthened under the Narendra Modi government, which wears its Hindi pride on its sleeve, and is now prompting even speakers of regional dialects to identify Hindi as their primary language.

A professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, who didn’t want to be named, said: “The data we are referring to was collected in 2010 and revised in 2011, before the BJP came to power. However, one reason for the spike now is the growing traction for the idea that is a keystone of the BJP ideology – Hindi as a central element of national identity. This idea does seem to have found takers among more individuals, even those from non-Hindi-speaking backgrounds, who are beginning to identify with Hindi, not necessarily due to their linguistic roots, but because the socio-political environment has increasingly normalised and elevated Hindi as a unifying national language.”

According to the professor, the upcoming Census exercise “will reflect a significant rise in the number of people who declare Hindi as their mother tongue”.

Political implications

While the demographic change in favour of native Hindi speakers in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) has the potential to shift political power, it has not yet translated into direct political dominance by North Indian migrants. Only 11 of the 36 MLAs elected from Mumbai are non-Maharashtrians.

Interestingly, in the early 1980s, this number used to be double, at 22. And in the 1970s, nearly 60% of all elected MLAs from Mumbai were non-Marathi speakers.

However, the nativist agenda of the Shiv Sena, which painted everyone apart from native Marathi speakers as outsiders, seems to have ended that trend, tilting the political landscape of the city decisively in favour of Marathi speakers.